|

political parties (ch 9)

What they say they stand for: 2008 party platforms of the Democrats and Republicans.

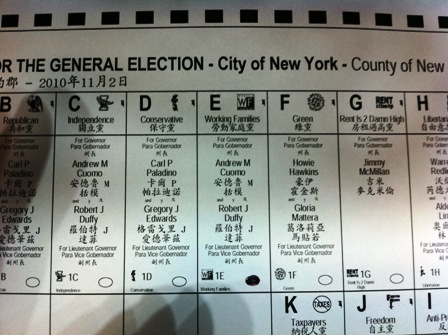

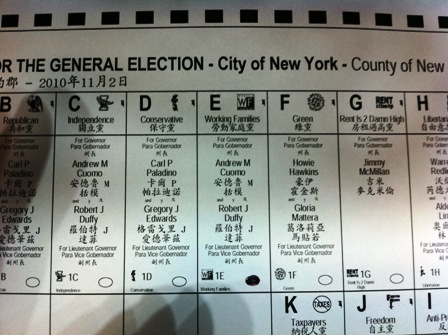

NYC ballot 2010 including the Working Families and Rent is 2 Damn High slates (courtesy of my son)

Points to ponder:

- Political parties, def. as “organizations with a label that try to place their members in office,” are said to have four functions: 1) get their members elected to office (the primary, essential function); 2) organize like-minded people in the electorate and in government; 3) serve as a cue for voters, especially in low-information campaigns; 4) identify and train future political leaders (recruitment)

- political parties are one kind of (what is called by some political scientists) linkage institution in that political parties link citizens to the government and government officials

- interest groups are another kind of linkage institution, but they have, as will be seen when they are taken up in the next topic, a different function, getting their preferred policies adopted by government

- some political scientists also include media and elections as linkage institutions

- one way to think of parties in terms of their primary function, getting their members elected is office, is as vote-sucking machines; in making any decision, party leaders think, "will doing X win more votes or lose more votes?"

- in the organizing like-minded people vein

- in the electorate, citizens will look to parties as a place to find people with similar views with whom they might collaborate, or whom they might mobilize, to advance their interests

- in government, party is used, among other ways, to organize Congress and by the president in making appointments to control the bureaucracy and the judiciary

- because most citizens are not highly engaged in politics (they typically are not highly interested nor highly informed) the party label provides a cheap and easy way to evaluate candidates and policies; think about a voter who is a Democrat facing an election for county coroner--who is the better candidate when a voter doesn't know the candidates, doesn't know which would be a better coroner, and isn't even sure exactly what the coroner does: using party as a cue, the voter follows the simple rule, "when in doubt, vote Democratic"

- from the recruitment perspective, parties are important for identifying potentially strong candidates/officeholders, training them in various political skills (campaigning, negotiating, decisionmaking), and also screening out those with liabilities; Bill Clinton, a consummate politician by almost any account (aside from certain personal weakhess, which show that parties don't always screen successfully), had a long apprenticeship in Democratic politics--worker in the Washington office of Senator J. William Fulbright (D, AR), Texas campaign coordinator for Democratic presidential candidate McGovern in 1972, unsuccessful Democratic candidate for the US House (4th district, AR), successful Democratic candidate for Arkansas Attorney-General, successful Democratic candidate for Arkansas Governor (though defeated in his first re-election bid, he came back, having learned some lessons, to retake the Governor's Mansion), disastrous speaking engagement at the 1988 Democratic National Convention (failing tests is part of the learning process), chair of the Democratic Governors Association, and leadership of the reformist Democratic Leadership Council

- Federalism is a characteristic of US political parties, which are really national unions of party organizations in the fifty states, though as Coleman et al. point out (347-49) the national parties are offering technical services to the state organizations that may increase national office influence

- One can distinguish between party activists who participate in primaries and caucuses to select party nominees for office and party supporters (voters who are not so involved but who, because of an attachment to the party [party identification] are likely to vote for their party’s nominee); it turns out that Democratic party activists tend to be further to the left than are Democratic party supporters (and Republican party activists are further to the right than are Republican party supporters).

- The use of primaries and caucuses, in place of party-boss controlled conventions, has decentralized (some say, democratized) the candidate selection process; on the other hand, party bosses typically were less interested in policy than in winning elections, which meant that they were motivated to find candidates who would have wide appeal; the decentralization of the candidate selection process allows highly motivated activists who are committed to a particular policy position or a particular candidate to dominate the process of choosing candidates, but they may be responsible for nominating candidates with little broad appeal.

- Recall the meaning of party identification and how it is measured; to see what happens when you make it easy for respondents to say answer “no opinion” or “don’t know,” consider a paper from Knowledge Networks; the paper is a nice demonstration that “forcing” choices tends to reduce the number of those picking the “safe” position (in this case, independent).

Questions to consider:

-

While “third parties” exist and occasionally generate a certain amount of attention, the US has essentially a two-party system and a two-party system that is well-established with two political parties dominating the system for nearly 150 years. Why are we pretty much stuck with the Democrats and Republicans? Tweedledum and Tweedledummer. Why do we not have other, newer choices?

-

Suppose a survey researcher asks you the standard NES party identification question: How would answer? And how is it that you come to the category you do?

|